ABSTRACT

Global emissions of fluorinated greenhouse gases (F-gases) and ozone-depleting substances (ODS), together represent almost five per cent of total greenhouse gases. On 7 February 2024, the European Union (EU) published new rules to limit F-gases and ODS emissions, which include a complete phase-out of hydrofluorocarbons (HFCs), new measures to strengthen compliance and combat illegal trade, new measures to address concerns over hydrofluoroolefins (HFOs) as per- and poly-fluoroalkyl substances (PFAS) and measures to monitor and address emissions of ODS used as feedstocks.

This paper describes these new measures and their relevance for global efforts to reduce GHG emissions under the Montreal Protocol to meet the climate challenge.

NEW EU RULES TO ACCELERATE HFC AND ODS EMISSION REDUCTIONS

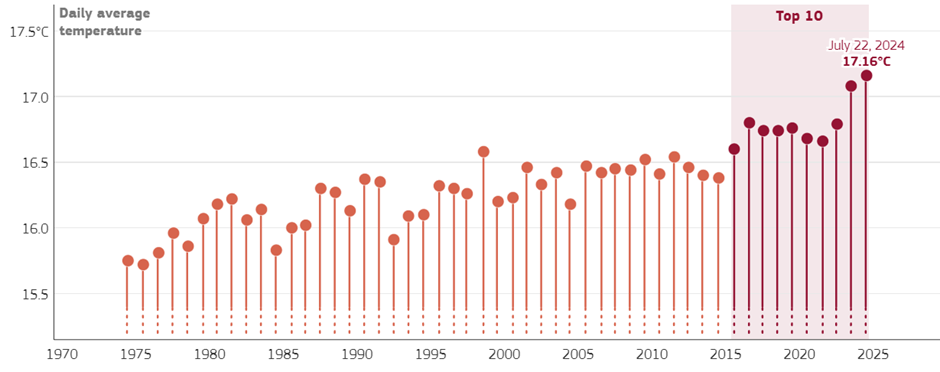

Global temperatures are rising and the urgent need to address climate change has never been clearer. In 2023, temperatures soared to the highest ever recorded, at 1.18°C above the 20th century average1. The ten highest annual maximum global daily temperatures of the last 50 years have all occurred in the last ten years, with 22 July 2024 recorded as the hottest on record2. As stated by UN Secretary-General António Guterres, “The era of global warming has ended; the era of global boiling has arrived.”3 The world’s leading climate scientists are warning that global heating could rocket past 1.5°C, bringing with it famine, conflict and mass migration driven by far more intensive heatwaves, wildfires and storms4.

Fluorinated greenhouse gases (F-gases) and ozone depleting substances (ODS) known as chlorofluorocarbons (CFCs) and hydrofluorocarbons (HCFCs) together represent almost five per cent of total greenhouse gas emissions5. Many of these chemicals are short-lived climate pollutants, acting rapidly and devastatingly on near-term climate change. Given that sustainable and climate-friendly alternatives exist for most uses of these synthetic chemicals, their swift replacement is an obvious priority in climate mitigation action plans.

On January 29, 2024, the European Union (EU) adopted comprehensive new rules to limit emissions of F-gases and ODS. Described as the “the most ambitious in the world” by Wopke Hoekstra, EU Commissioner for Climate Action, the revision of the previous EU F-gas Regulation significantly strengthens controls on hydrofluorocarbons (HFCs) and is expected to avoid approximately 500 million tonnes of carbon dioxide equivalence (CO2e) by 20506.

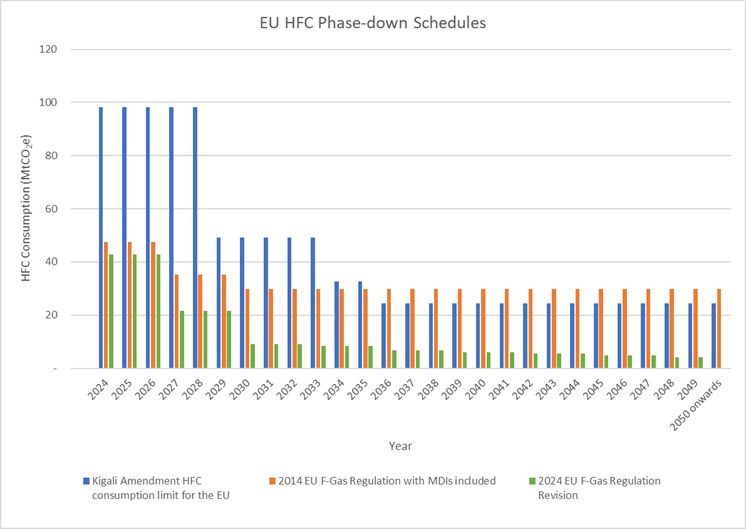

The new F-gas Regulation is underpinned by an accelerated reduction of HFCs to a complete phase-out in 2050, far exceeding the ambition of the mandated global schedule under the Kigali Amendment to the Montreal Protocol. Additional measures aimed at guiding and enforcing the phase out include further actions to counter illegal trade, allocation fees for HFC quotas, additional bans on new HFC-based equipment in key sectors (including air-conditioning, heat pumps and refrigeration), a prohibition on dumping outdated high-GWP HFC-based equipment in non-EU countries, and mandatory training and certification of technicians on natural refrigerants, such as carbon-dioxide, hydrocarbons, ammonia and water.

In addition, the Regulation seeks to avoid the unnecessary uptake of hydrofluoroolefins (HFOs), which have been promoted as alternatives to HFCs due to their lower Global Warming Potential (GWP), but are raising major concerns globally due to their industrial emissions during manufacture and environmental impact, particularly their role as, or potential to degrade into, per- and poly-fluoroalkyl substances (PFAS), which are persistent and toxic ‘forever chemicals’7. The new EU measures include provisions to address these concerns by monitoring the use of HFOs and encouraging the development and adoption of safer alternatives through bans on all fluorinated gases in certain sectors8.

Through the review of the ODS Regulation, the EU has also recognised the continued “significant threat to health and the environment” from increased ultraviolet (UV) radiation due to depletion of the ozone layer. The new EU ODS regulation responds to the need for additional action to address continued ODS emission sources, both to prevent further ozone depletion and – given that most ODS have a high Global Warming Potential (GWP) – to help meet the goals of the Paris Agreement9. ODS production in the EU increased by 27% from 2020-21, primarily (90%) due to use as feedstocks – as building blocks in the manufacture of other chemicals. The new EU ODS Regulation recognises that there is a need to assess emission levels as well as the availability of alternatives to using ODS as feedstocks. In response to this, the Regulation allows the European Commission to establish a list of chemical production processes for which the use of ODS will be prohibited on the basis of technical assessments carried out under the Montreal Protocol or, failing that, on the basis of its own assessment by the end of 202710.

To ensure the effectiveness of the new regulations, the EU has also introduced measures to strengthen compliance and combat illegal trade in F-gases and ODS. These include stricter monitoring and enforcement mechanisms, as well as increased penalties for non-compliance. By addressing illegal trade, which undermines regulatory efforts, the EU aims to create a level playing field and ensure that all stakeholders adhere to the new standards.

RELEVANCE TO GLOBAL EFFORTS UNDER THE MONTREAL PROTOCOL

Widely hailed as the world’s most successful international environmental treaty, the Montreal Protocol has played a critical role in mitigating climate change for more than 35 years. The ODS phase-out under the Montreal Protocol has set the ozone layer on the path to recovery, protecting the world’s biosphere from harmful UV radiation and avoiding significant global warming – as much as 2.5°C by 2100, taking into account the avoidance of significant negative impacts of UV radiation on the terrestrial biosphere’s capacity as a carbon sink11.

Despite this undeniable success, the Montreal Protocol has much more to do and more to offer in meeting our global climate targets12. In addition to strengthening the institutions and processes of the Protocol to ensure sustained compliance, the Protocol can deliver significant additional climate mitigation through strengthening measures to mitigate HFC and ODS emissions.

The landmark 2016 Kigali Amendment, which formally established the Montreal Protocol as a climate treaty too, aims to phase down the production and consumption of HFCs by about 85% by 2045, with several different schedules and groupings of countries. Although implementation of the Kigali Amendment is only just underway, it is clear that the current phase-down schedules are not consistent with IPCC 1.5°C scenarios13. Analysis of country data reveals that the baseline set for Article 5 Parties (developing countries) is artificially high, leaving scope for many countries to continue growing their HFC consumption throughout most of the current decade while remaining technically compliant with the Kigali phase-down controls14. Likewise, the fact that EU consumption of HFCs in 2022 was already less than half (45%) of the maximum imposed by the Montreal Protocol, demonstrates clearly the lack of ambition in the non-A5 (developed country) Kigali Amendment schedule15.

The EU F-gas Regulation will spearhead the transition away from HFCs to natural refrigerants, paving the way for the global transition in other countries and setting the stage for more ambitious action at the Montreal Protocol to accelerate the global phase-down of HFCs.

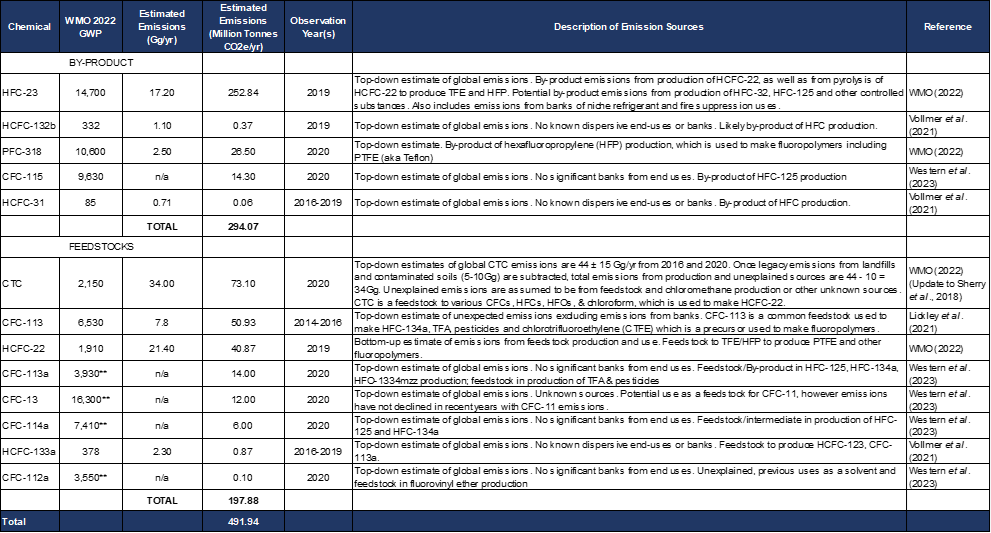

At the same time, significant and unexpected global emissions of phased-out ODS are being reported with increasing frequency by atmospheric scientists. By collating recently published papers reporting on primarily feedstock and byproduct emissions, EIA estimates almost half a billion tonnes of carbon dioxide-equivalent emissions (491.94 GtCO2e) each year are linked to unregulated fluorochemical industrial processes16. Of these emissions, about 60% are related to byproduct emissions, primarily HFC-23, while 40% are related to feedstock emissions (see Fig 3). Feedstock ODS and HFCs are exempt from Montreal Protocol controls, based on the assumption that emissions were ‘negligible’. In recent years however, the Montreal Protocol has begun to examine concerns that this is not the case.

An Australia-led initiative at the 35th Meeting of the Parties in 2023 resulted in a decision requesting the Protocol’s Technology and Economic Assessment Panel to provide an update on the emissions from feedstock production and use, including sources of such emissions, available alternatives, best practices and technologies for minimising emissions17. The TEAP report, published in May 2024, shows that emissions are in fact significant, but the work of the Panel has been severely hampered by the lack of transparency and accountability around fluorochemical production18.

Emissions of HFC-23, a by-product from the production of HCFC-22 (which is by far the most common feedstock chemical) are of particular concern. These emissions are extremely high (representing 15% of the radiative forcing of all HFCs), have rapidly increased in recent years and are significantly larger than expected given reported mitigation measures (17.2 ± 0.8 vs 2.2 kt/yr in 2019)19.

Early EU implementation of the new feedstock provisions under the EU ODS Regulation could provide valuable information and a model for initial steps to take to better control feedstock emissions. Similarly, there are measures in both the EU ODS and F-Gas regulations to reduce HFC-23 emissions. The EU F-gas Regulation has prohibited placing on the market of new fire protection equipment containing HFC-23 since 201620. Both regulations require producers and, importantly, importers placing F-gases or ODS on the EU market to provide evidence that any HFC-23, produced as a by-product during the production of the F-gas (including the production of the feedstock for the production of that gas) has been destroyed or recovered for subsequent use, using best available techniques21. These measures could be replicated around the world to provide greater incentives for producers to destroy the super pollutant byproduct.

Ironically, much of the ODS feedstock use that is causing greater emissions of ODS, as well as HFC-23 byproduct, is linked to the production of so-called ‘climate-friendly’ HFOs. By avoiding these fourth generation fluorochemicals – which are PFAS and are also degrading to HFC-23 in the atmosphere22– and prioritising the uptake of sustainable natural refrigerant technologies, the Montreal Protocol and its Multilateral Fund could also address a considerable part of the feedstock problem at source and further reduce HFC-23 emissions.

CONCLUSION

The year 2023 underscored the urgency of addressing climate change, with record-breaking temperatures highlighting the need for immediate and decisive action. The European Union’s adoption of new rules to limit emissions of F-gases and ODS represents a significant step in this direction. By phasing out HFCs, strengthening compliance measures, reducing emissions from ODS feedstocks, and addressing concerns over HFOs, the EU is taking comprehensive action to reduce its greenhouse gas emissions.

By demonstrating that it is possible to phase out harmful substances while maintaining industrial competitiveness, the EU provides a model that other countries can follow. This could lead to a broader, more coordinated global effort to reduce emissions of high-GWP substances, and ultimately an acceleration of the Kigali Amendment to place it in line with our global climate targets.

The EU’s new regulations also enhance the effectiveness of the Montreal Protocol by addressing emerging concerns, such as the environmental impact of HFOs and emissions from ODS feedstocks. By incorporating these issues into its regulatory framework, the EU is helping to ensure that the Montreal Protocol remains relevant and effective in the face of evolving scientific understanding and environmental challenges and makes a meaningful impact in the fight against climate change.

References

- NOAA National Centers for Environmental Information. 17 January 2024. 2023 was the warmest year in the modern temperature records. Available here ↩︎

- Copernicus Climate Change Service. New record daily global average temperature reached in July 2024. 25 July 2024. Available here ↩︎

- UN Secretary-General’s opening remarks at press conference on climate. 27 July 2023. Available here ↩︎

- Carrington, D. (2024). World’s top climate scientists expect global heating to blast past 1.5°C target. The Guardian. Available here ↩︎

- IPCC, 2022: Climate Change 2022: Mitigation of Climate Change. Contribution of Working Group III to the Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change [P.R. Shukla, J. Skea, R. Slade, A. Al Khourdajie, R. van Diemen, D. McCollum, M. Pathak, S. Some, P. Vyas, R. Fradera, M. Belkacemi, A. Hasija, G. Lisboa, S. Luz, J. Malley, (eds.)]. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, UK and New York, NY, USA. https://doi.org/10.1017/9781009157926 (p59); World Meteorological Organization (WMO). Scientific Assessment of Ozone Depletion: 2022, GAW Report No. 278, 509 pp.; WMO: Geneva, 2022 (p67). Available here ↩︎

- European Commission (2024) “Commission welcomes adoption of ambitious rules to limit fluorinated gases and ozone depleting substances” Press release. 29 January 2024. Available here. ↩︎

- European Chemical Agency. Per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFASs). Available here. ↩︎

- For example, all F-gases will be prohibited in small self-contained air-conditioning and heat pump equipment from 2032 and small split systems from 2035, in all domestic fridges and freezers from 2026, small chillers from 2032, fire protection and personal care products from 2024, foams from 2033, technical aerosols from 2030. See Regulation (EU) No 2024/573, Annex IV ↩︎

- Regulation (EU) 2024/590 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 7 February 2024 on substances that deplete the ozone layer. Available here ↩︎

- Article 6 (2), Regulation (EU) 2024/590 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 7 February 2024 on substances that deplete the ozone layer. Available here ↩︎

- Young, P.J., Harper, A.B., Huntingford, C. et al. 2021. The Montreal Protocol protects the terrestrial carbon sink. Nature 596, 384–388. Available here ↩︎

- Perry, C., Nickson, T., Starr, C., Grabiel, T., Geoghegan, S., Porter, B., … Walravens, F. (2024). More to offer from the Montreal protocol: how the ozone treaty can secure further significant greenhouse gas emission reductions in the future. Journal of Integrative Environmental Sciences, 21(1). https://doi.org/10.1080/1943815X.2024.2362124 ↩︎

- Purohit, P., Borgford-Parnell, N., Klimont, Z. et al. Achieving Paris climate goals calls for increasing ambition of the Kigali Amendment. Nat. Clim. Chang. 12, 339–342 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41558-022-01310-y ↩︎

- EIA (2024). Half-day session for an informal discussion on strategic approaches to Kigali Amendment implementation. Briefing to the 94th meeting of the Executive Committee to the Multilateral Fund. Available here ↩︎

- ETC CM report 2023/24. Fluorinated greenhouse gases 2023. Available here ↩︎

- EIA (2023). Plugging the Gaps in the Ozone Treaty: Addressing Fluorochemical Feedstock Emissions. Briefing to the UN Climate Change Conference COP28. Available here. ↩︎

- Decision XXXV/8: Feedstock uses Available here ↩︎

- See p74 & p79 in UNEP (2024) Report of the Technology & Economic Assessment Panel Vol 1: Progress Report. May 2024 Available here ↩︎

- Presentation by S. Montzka for the Scientific Assessment Panel at the 45th Open Ended Working Group of the Montreal Protocol. Available here ↩︎

- See Annex 4(11b) of Regulation (EU) 2024/590 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 7 February 2024 on substances that deplete the ozone layer. Available here ↩︎

- Article 4(6) Regulation (EU) 2024/590 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 7 February 2024 on substances that deplete the ozone layer. Available here and Article 15(4) of Regulation (EU) 2024/590 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 7 February 2024 on substances that deplete the ozone layer. Available here ↩︎

- Perez-Peña et al. (2023). Assessing the atmospheric fate of trifluoroacetaldehyde (CF3CHO) and its potential as a new source of fluoroform (HFC-23) using the AtChem2 box model. Environ. Sci.: Atmos., 2023, 3, 1767. Available here ↩︎

Clare Perry